Week 2: User stories, Tasks and Habits

SCRUM Week 2

📘 Summary: SCRUM Week 2 - User stories, Tasks and Habits

In Scrum Agile, the effective management of user stories, tasks, and habits plays a pivotal role in achieving successful sprint deliveries.

User stories, often expressed as Product Backlog Items (PBIs), drive the development process by focusing on end-user needs. They keep the team oriented towards problem-solving and encourage collaboration, creativity, and momentum. Writing user stories involves defining the “done” state, outlining subtasks, considering user personas, and incorporating ordered steps.

Tasks, specific actionable pieces of work, contribute to completing PBIs during a sprint. They break down work, promote collaboration, and provide clarity on incremental product delivery. The INVEST criteria guide the creation of quality PBIs, emphasizing characteristics like independence, negotiability, and value.

Planning poker, a consensus-based estimation technique, aids in assigning story points to tasks. While popular, it has potential drawbacks, such as time consumption and potential biases, necessitating a balance between efficiency and precision.

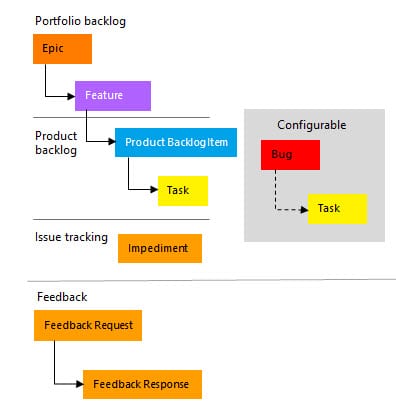

Themes and epics categorize stories by business goals and serve as larger requirements, respectively. User stories or work items are components of epics, and tasks contribute to building stories. Developing good habits is essential, and James Clear’s “Atomic Habits” provides a proven framework for habit formation, emphasizing identity-based habits and the habit loop.

Keywords: SCRUM Week 2 - User stories, Tasks and Habits

User stories, Tasks, Habits, Sprint deliveries, Product Backlog Items (PBIs), Planning poker, INVEST criteria, Themes, Epics, Definition of Done (DoD), Acceptance Criteria, Incremental product delivery.

Agile and Scrum is a User Story or Product Backlog Item (PBI) driven approach, this approach is overcoming some of the major notches in delivering the product that customer is seeking to have.

1 User stories

A user story is an informal, natural language description of features of a software system. They are written from the perspective of an end user or user of a system, and may be recorded on index cards, Post-it notes, or digitally in project management software.

User stories serve a number of key benefits:

- Stories keep the focus on the user. A to-do list keeps the team focused on tasks that need to be checked off, but a collection of stories keeps the team focused on solving problems for real users.

- Stories enable collaboration. With the end goal defined, the team can work together to decide how best to serve the user and meet that goal.

- Stories drive creative solutions. Stories encourage the team to think critically and creatively about how to best solve for an end goal.

- Stories create momentum. With each passing story, the development team enjoys a small challenge and a small win, driving momentum.

1.1 How to write user stories

Consider the following when writing user stories:

- Definition of “done” — The story is generally “done” when the user can complete the outlined task, but make sure to define what that is.

- Outline subtasks or tasks — Decide which specific steps need to be completed and who is responsible for each of them.

- User personas — For whom? If there are multiple end users, consider making multiple stories.

- Ordered Steps — Write a story for each step in a larger process.

- Listen to feedback — Talk to your users and capture the problem or need in their words. No need to guess at stories when you can source them from your customers.

- Time — Time is a touchy subject. Many development teams avoid discussions of time altogether, relying instead on their estimation frameworks. Since stories should be completable in one sprint, stories that might take weeks or months to complete should be broken up into smaller stories or should be considered their own epic.

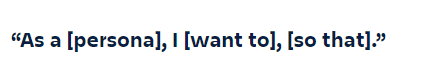

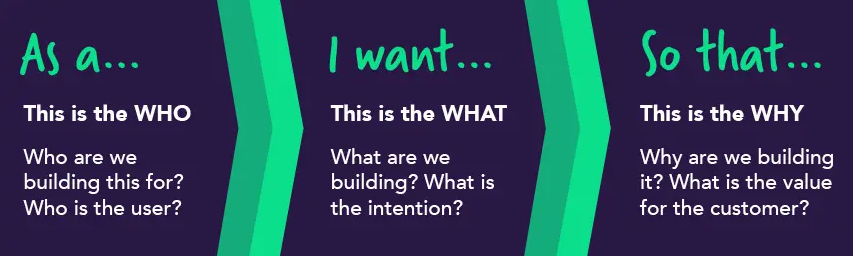

1.2 User story templates

- “As a [persona]”: Who are we building this for? We’re not just after a job title, we’re after the persona of the person. Max. Our team should have a shared understanding of who Max is. We’ve hopefully interviewed plenty of Max’s. We understand how that person works, how they think and what they feel. We have empathy for Max.

- “Wants to”: Here we’re describing their intent — not the features they use. What is it they’re actually trying to achieve? This statement should be implementation free — if you’re describing any part of the UI and not what the user goal is you’re missing the point.

- “So that”: how does their immediate desire to do something this fit into their bigger picture? What’s the overall benefit they’re trying to achieve? What is the big problem that needs solving?

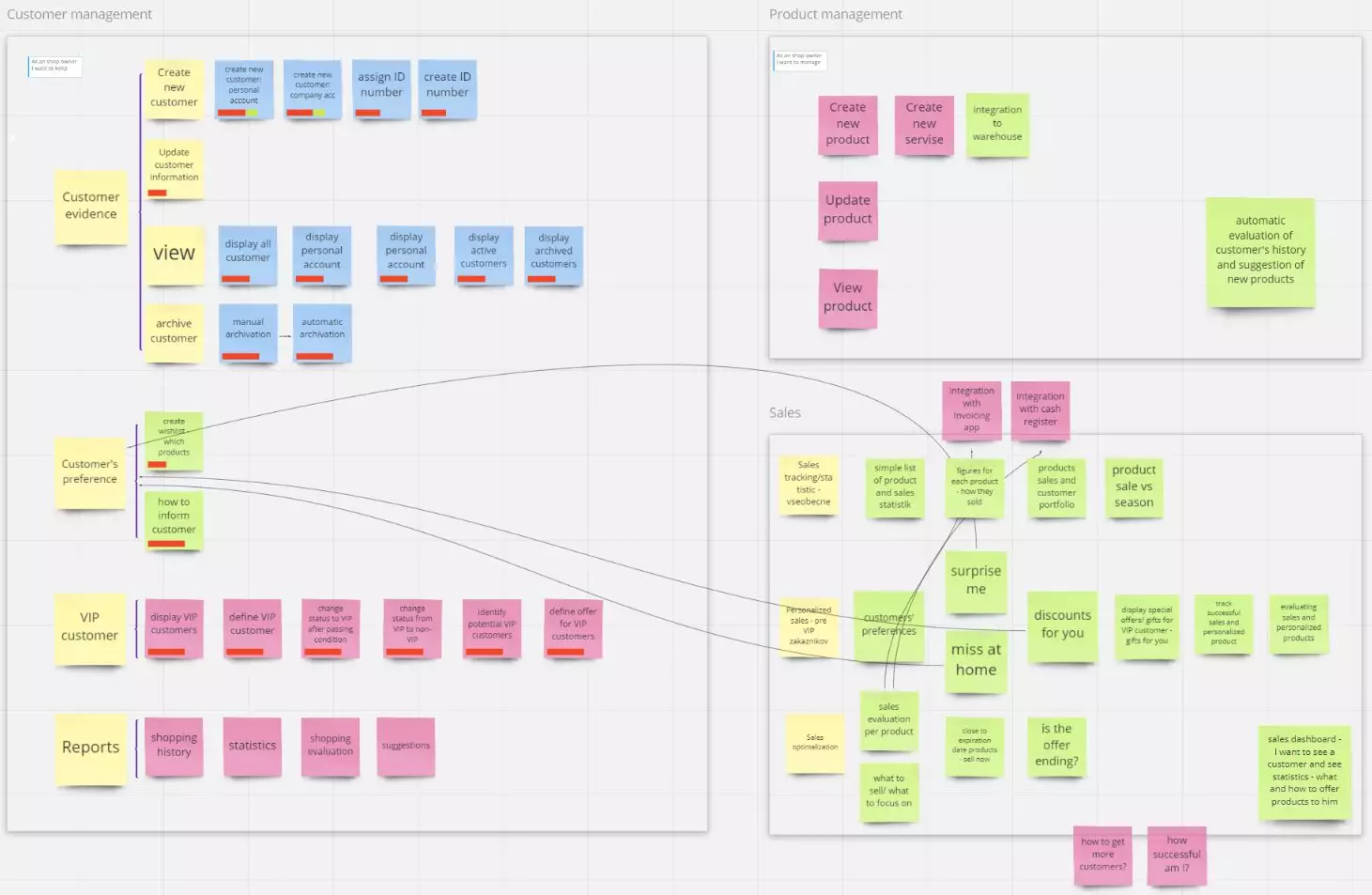

1.2.1 Scrum Alliance Website

The following example user stories were written to describe the functionality in an early version of the Scrum Alliance website. These stories were written in early 2004. Some stories are good, some aren’t.

1.3 Definition of Done vs Acceptance Criteria

Definition of Done (DoD) is a list of requirements that a user story must adhere to for the team to call it complete.

While the Acceptance Criteria of a User Story consist of set of Test Scenarios that are to be met to confirm that the software is working as expected.

2 Tasks

In Scrum Agile, a task is a specific, actionable piece of work that contributes to the completion of a Product Backlog Item (PBI) during a Sprint.

Tasks are detailed, time-boxed activities that team members take on to fulfill the requirements of a user story or feature. These tasks are often created during Sprint Planning and are meant to be small enough to be completed within the defined time frame of the Sprint. Tasks help break down the work, facilitate collaboration, and provide a clear understanding of the steps needed to deliver the product incrementally.

2.1 Invest

he INVEST mnemonic for Agile software development projects was created by Bill Wake as a reminder of the characteristics of a good quality Product Backlog Item (commonly written in user story format, but not required to be) or PBI for short.

Such PBIs may be used in a Scrum backlog, Kanban board, or XP project.

| Letter | Meaning | Description |

|---|---|---|

| I | Independent | The PBI should be self-contained. |

| N | Negotiable | PBIs are not explicit contracts and should leave space for discussion. |

| V | Valuable | A PBI must deliver value to the stakeholders. |

| E | Estimable | You must always be able to estimate the size of a PBI. |

| S | Small | PBIs should not be so big as to become impossible to plan/task/prioritize within a level of accuracy. |

| T | Testable | The PBI or its related description must provide the necessary information to make test development possible. |

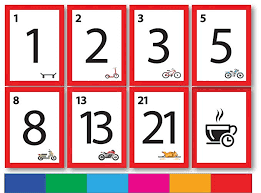

2.2 Planning poker

Planning poker, also called Scrum poker, is a consensus-based, gamified technique for estimating, mostly used for timeboxing in Agile principles.

In planning poker, members, estimators of the group make estimates by playing numbered cards face-down to the table, instead of speaking them aloud.

The use of the Fibonacci sequence (e.g., 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13) in estimation during Agile practices like Scrum is not rooted in neuroscience per se but is more aligned with cognitive and psychological principles. The Fibonacci sequence is often used to represent story points, which are a measure of effort or complexity.

Each estimator has a physical or virtual deck of cards. These Planning Poker cards display values like 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, 20, 40 and 100 (the modified Fibonacci numbers sequence). The values represent the number of story points, ideal days, or other units in which the team estimates.

So, the cards are revealed, and the estimates are then discussed. By hiding the figures in this way, the group can avoid the cognitive bias of anchoring, where the first number spoken aloud sets a precedent for subsequent estimates.

2.3 Criticism

While Planning Poker is a popular estimation technique in Scrum, it has potential drawbacks.

It can be time-consuming, especially in larger teams, leading to extended planning sessions. The subjective nature of the method may result in biased estimates, as individuals with more influence can sway the consensus. Additionally, team members might hesitate to challenge senior members’ estimates, hindering accurate assessments.

Misinterpretation of story points and the gamification aspect may also undermine the seriousness of the process. Striking a balance between efficiency and precision is crucial to mitigate these issues and ensure Planning Poker’s effectiveness in Scrum.

3 Themes and Epics

3.1 Themes

A collection of stories by category. Like a jar for cookies, it’s a container of stories. By its nature, an epic can also be a theme in itself. They should refer to a business goal.

An example of a theme: “Agile Board”.

3.2 Epics

An epic is a larger story. A requirement that is too big to deliver in a single sprint and need to be broken into smaller deliverables (stories). Epics are progressively broken into a set of smaller user stories at the appropriate time.

An example epic: “As a team leader, I want to be have an agile SCRUM board so that I can easily manage the work of my team”.

3.3 User-Stories or just stories

Often referred to as Product Backlog Item or Work Item.

An example user story: “As a team leader, I want to be able to see tasks as cards on an agile SCRUM board so that I can easily see who’s working on what”.

3.4 Tasks

he elements that build up for a story. Some teams don’t divide their stories into tasks, as they prefer to work vertically. Splitting stories into tasks encourages teams to split work horizontally.

An example of a task: “Create collapse/expand buttons”.

Tasks often follow the SMART acronym: specific, measurable, achievable, relevant, time-boxed (although what the letters stand for seems to be hotly debated).

4 Habits

A habit is a routine of behavior that is repeated regularly and tends to occur subconsciously.

4.1 Atomic Habits

Atomic Habits: An Easy & Proven Way to Build Good Habits & Break Bad Ones

No matter your goals, Atomic Habits offers a proven framework for improving—every day. James Clear, one of the world’s leading experts on habit formation, reveals practical strategies that will teach you exactly how to form good habits, break bad ones, and master the tiny behaviors that lead to remarkable results.

If you’re having trouble changing your habits, the problem isn’t you. The problem is your system.

Bad habits repeat themselves again and again not because you don’t want to change, but because you have the wrong system for change. You do not rise to the level of your goals. You fall to the level of your systems. Here, you’ll get a proven system that can take you to new heights.

James Clear is known for his ability to distill complex topics into simple behaviors that can be easily applied to daily life and work. Here, he draws on the most proven ideas from biology, psychology, and neuroscience to create an easy-to-understand guide for making good habits inevitable and bad habits impossible.

Learn how to:

- Make time for new habits (even when life gets crazy);

- Overcome a lack of motivation and willpower;

- Design your environment to make success easier;

- Get back on track when you fall of

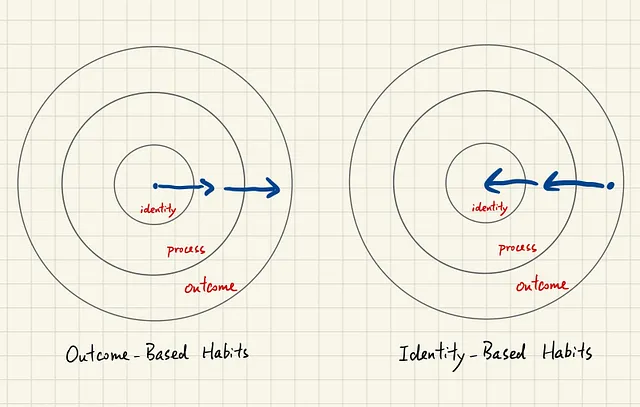

4.2 Build identity-based habits

The ultimate form of intrinsic motivation is when a habit becomes part of your identity.

If you want to build a reading habit, your goal is not to read books but to become a reader. If you want to build a running habit, your goal is not to run a marathon but to become a runner.

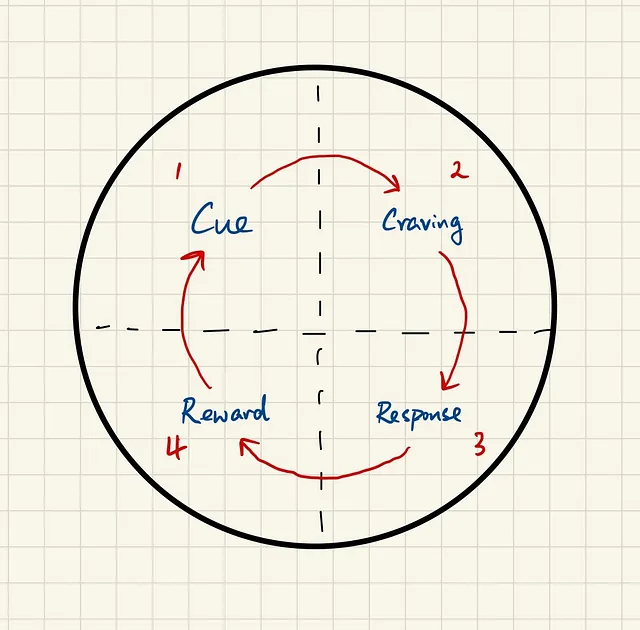

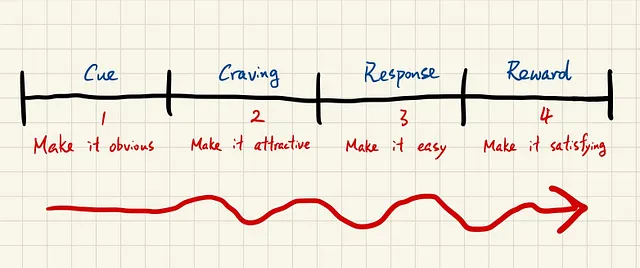

4.3 The Habit Loop

The cue triggers a craving. Then it motivates a response. And it provides a reward, which satisfies the craving and finally becomes associated with the cue.

- Cue

- Craving

- Response

- Reward