📘 Summary: SCRUM Week 11 - Team Dynamics

Team Dynamics of SCRUM explores the intricate dynamics of team interactions, drawing parallels from chimpanzee politics and human behavior.

Frans de Waal’s insights into chimp colonies reveal underlying power struggles reminiscent of human political maneuvering. The discussion on social hierarchies introduces the Status Game, encompassing Virtue, Competition, and Dominance games as strategies for securing social standing. The Minority Rules concept emphasizes the impact of determined minorities on societal norms. Milgram’s Experiments shed light on blind obedience to authority, exposing the perils of moral compromise.

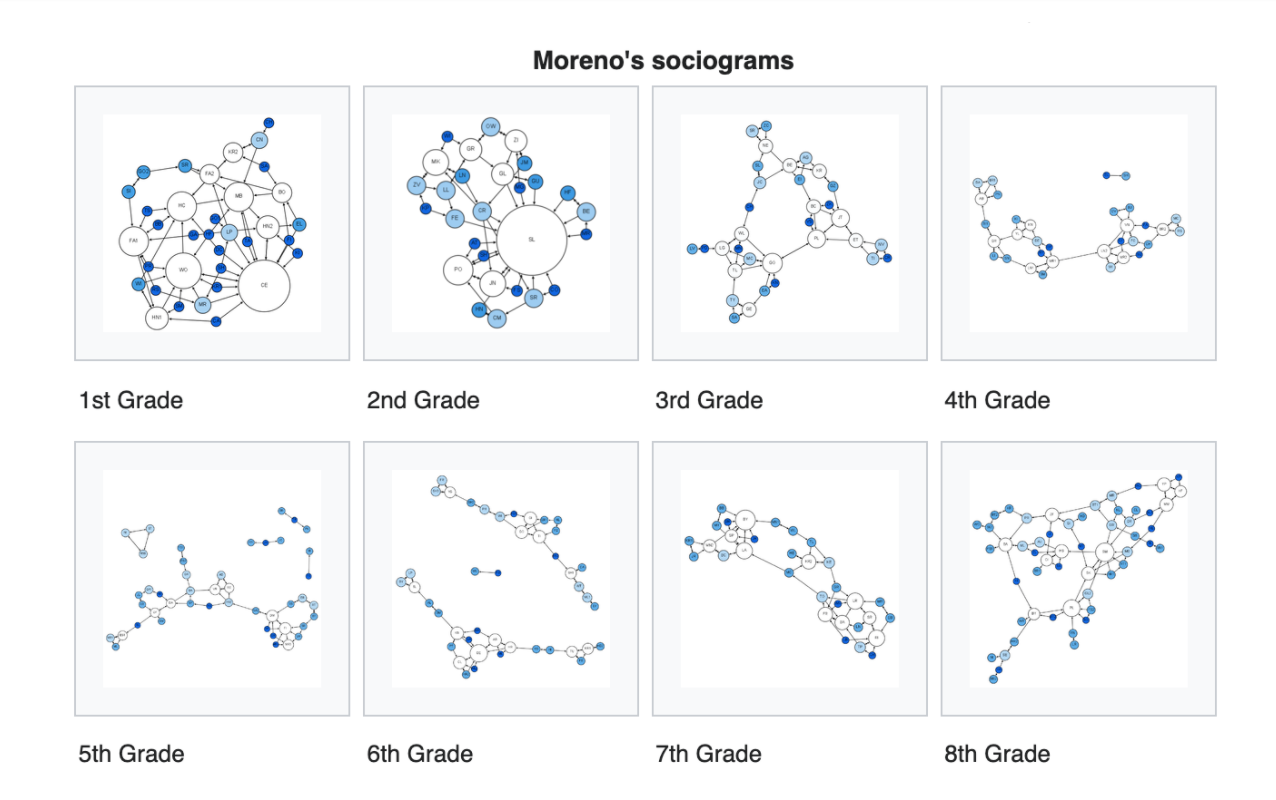

The introduction of the Sociogram as a tool for mapping group relationships enhances leaders’ understanding of team dynamics. Behavioral Economics, exemplified by Richard H. Thaler’s work, challenges traditional economic models, emphasizing the role of emotions in decision-making.

Keywords: SCRUM Week 11 - Team Dynamics

Team Dynamics, Frans de Waal, Social Hierarchies, Virtue Game, Competition Game, Dominance Game, Minority Rules, Nassim Nicholas Taleb, Milgram’s Experiments, Sociogram, Behavioral Economics, Richard H. Thaler, Nudges, Incentives

Origins

Social Organization

An incredible insight into the takeovers and social organization of a chimp colony in the Netherlands. “The behavior of our closest relatives provides clues about human nature. Apart from political maneuvering, chimpanzees show many behaviors that parallel those of humans, from tool technology to intercommunity warfare. In fact, our place among the primates is increasingly a backdrop of substantial similarity. Our uniqueness breaks down as we study our relatives.

Every country has its Dick Cheneys and Ted Kennedys operating behind the scenes.

Being over the hill themselves, these experienced men often exploit the intense rivalries among younger politicians, gaining tremendous power as a result. I also did not draw explicit parallels between how rival chimpanzees curry favor with females by grooming and tickling their young and the way human politicians hold up and kiss babies, something they rarely do outside the election season.

There are tons of such parallels, also in nonverbal communication (the swaggering, the lowering of voices), but I stayed away from all these. To me, they were so obvious I am happy to leave them to my readers…The social dynamics are essentially the same. The game of probing and challenging, of forming coalitions, of undermining others’ coalitions, and of slapping the table to reinforce a point is right there for any observer to see.

The will to power is a human universal. Our species has been engaged in Machiavellian tactics since the dawn of time, which is why no one should be surprised about the evolutionary connection pointed out in the present book.”

Social dynamics

The status game

The Status Game roots

The Status Game often involves social interactions where individuals seek to establish and maintain their position within a social hierarchy. Key concepts within this realm include:

Social Hierarchies: Understanding societies’ hierarchical structures and navigating to secure one’s position.

Symbolic Capital: Accumulating resources, attributes, or achievements that confer status within a social context.

Social Comparison: Constant assessment of one’s status relative to others, driving behaviors and choices.

Understanding Status Games: Virtue, Competition, and Dominance

In the realm of status games, three prominent games often come to the forefront:

Virtue Game: In the Virtue Game, individuals seek status through moral and ethical excellence. Displaying qualities such as honesty, integrity, and altruism becomes a means to elevate one’s standing in social hierarchies.

Competition Game: The Competition Game revolves around outperforming peers in various domains, including career achievements, skills, or talents. Success in this game is often measured by surpassing others in a competitive environment.

Dominance Game: The Dominance Game involves asserting power and control to secure a higher status. Individuals may employ tactics such as influence, authority, or manipulation to establish dominance and command respect within social structures.

These three games collectively illustrate the diverse strategies individuals employ to navigate social hierarchies and gain recognition within their communities.

Each game reflects different values, priorities, and approaches to achieving status in a given context.

Minority Rules: the super-pareto

The Minority Rules concept, popularized by Nassim Nicholas Taleb, suggests that a small, committed minority can have a disproportionate impact on a larger population. Taleb argues that throughout history, transformative ideas or behaviors often originated from a determined minority, influencing the majority.

This phenomenon contrasts with traditional democratic views. Taleb emphasizes the power of persistence and conviction, positing that even a small group with strong beliefs can shape societal norms. The Minority Rules principle underscores the nonlinear nature of influence, where committed outliers, rather than conformist majorities, drive significant societal changes.

The main idea behind complex systems is that the ensemble behaves in ways not predicted by the components. The interactions matter more than the nature of the units.

Studying individual ants will never (one can safely say never for most such situations), never give us an idea on how the ant colony operates. For that, one needs to understand an ant colony as an ant colony, no less, no more, not a collection of ants.

This is called an “emergent” property of the whole, by which parts and whole differ because what matters is the interactions between such parts. And interactions can obey very simple rules.

The rule we discuss in this chapter is the minority rule.

The minority rule will show us how it all it takes is a small number of intolerant virtuous people with skin in the game, in the form of courage, for society to function properly.

Milgram’s Experiments and the Perils of Obedience

Milgram’s Experiments, conducted by psychologist Stanley Milgram in the 1960s, aimed to study obedience to authority figures. Participants were instructed to administer increasingly severe electric shocks to a person (a confederate) in another room, even when protests were heard.

The shocks were simulated, but the study revealed the alarming extent to which people would comply with authority, even when it conflicted with their moral beliefs.

This highlighted the perils of blind obedience, illustrating the potential for individuals to engage in harmful actions under authoritative influence. Milgram’s work raised ethical concerns but significantly contributed to our understanding of human behavior in social contexts.

Behavioral Economics

Behavioral Economics merges insights from psychology and economics to understand how individuals deviate from rational decision-making. It explores cognitive biases, emotional influences, and social factors, providing a more realistic framework for analyzing economic behavior. Researchers like Richard H. Thaler have contributed significantly to this field, challenging traditional economic models.

From Cashews to Nudges: The Evolution of Behavioral Economics

Richard H. Thaler’s “From Cashews to Nudges: The Evolution of Behavioral Economics” Prize Lecture, delivered on December 8, 2017, at the University of Chicago Booth School of Business, explores the progression of behavioral economics.

Thaler, a pioneer in the field, traces its evolution from early anomalies like cashew consumption patterns to the development of behavioral insights that underpin “nudges” – subtle interventions designed to influence decision-making.

The lecture likely delves into how these insights challenge traditional economic models and reshape our understanding of how individuals make choices, offering a nuanced perspective on the intersection of psychology and economics in decision science.

Richard H. Thaler’s insights in behavioral economics challenge traditional economic assumptions. He introduces concepts like bounded rationality and loss aversion, demonstrating that decision-making is influenced by cognitive limitations and emotional factors.

Thaler’s work includes the popularized idea of “nudging,” subtle interventions guiding individuals toward better choices. By recognizing these behavioral patterns, policymakers can design effective strategies for public policy and individuals can make more informed economic decisions.

Regarding Thaler: How Do We Make Economic Decisions?

Richard H. Thaler, a prominent figure in behavioral economics, has reshaped our understanding of how individuals make economic decisions. His work challenges the traditional assumption of perfect rationality, introducing insights from psychology and behavioral science. Key concepts include:

- Bounded Rationality:

- Acknowledges limited cognitive resources, leading to heuristics and systematic biases.

- Loss Aversion:

- Highlights the tendency to weigh potential losses more heavily than equivalent gains, influencing decision-making and risk-taking.

- Nudging:

- Introduces the concept that subtle changes in choice presentation (“nudges”) can impact decisions and guide individuals toward better outcomes.

- Behavioral Economics and Policy:

- Examines the implications for public policy, using insights to design interventions that encourage better choices.

- Endowment Effect:

- Explores how individuals assign higher value to owned items, affecting economic decisions.

Thaler’s contributions emphasize that economic decision-making is influenced by cognitive limitations, emotions, and social context. Recognizing these behavioral patterns allows for a more realistic understanding and the design of strategies to improve decision outcomes.

Back to top

1.1 Social Organization

Every country has its Dick Cheneys and Ted Kennedys operating behind the scenes.

Being over the hill themselves, these experienced men often exploit the intense rivalries among younger politicians, gaining tremendous power as a result. I also did not draw explicit parallels between how rival chimpanzees curry favor with females by grooming and tickling their young and the way human politicians hold up and kiss babies, something they rarely do outside the election season.

There are tons of such parallels, also in nonverbal communication (the swaggering, the lowering of voices), but I stayed away from all these. To me, they were so obvious I am happy to leave them to my readers…The social dynamics are essentially the same. The game of probing and challenging, of forming coalitions, of undermining others’ coalitions, and of slapping the table to reinforce a point is right there for any observer to see.

The will to power is a human universal. Our species has been engaged in Machiavellian tactics since the dawn of time, which is why no one should be surprised about the evolutionary connection pointed out in the present book.”